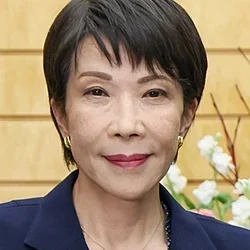

NAIROBI, Kenya — In a small workshop outside Nairobi, Mary Mwangi is tackling a problem many breast-cancer survivors in Kenya face quietly: how to rebuild confidence and daily comfort after a mastectomy without the high cost of conventional prostheses.

Mwangi, herself a survivor of spinal and breast cancer, says she returned to knitting during treatment as a way to manage stress and loss of income. What began as therapy became a social enterprise after her double mastectomy, when she encountered stigma and saw other women enduring similar emotional and financial burdens in silence.

Her solution is simple: hand-knitted breast prostheses made in different sizes and skin tones, filled with yarn and worn inside adapted bras with pockets. Mwangi says smaller pieces can take about 15 minutes to make, while larger ones take around 30 minutes—fast production that keeps prices low and access broad.

The affordability gap is stark. Local reporting on the initiative says knitted prostheses sell for roughly $11, compared with around $170 for silicone alternatives—placing standard options out of reach for many households.

But for Mwangi, the project is about more than price. She runs regular group sessions where women learn to knit prostheses, share recovery experiences, and support one another through body-image changes and post-treatment anxiety. Survivors describe the classes as both practical and therapeutic—part skills training, part peer counseling.

The need is significant. Breast cancer remains one of the most common cancers among women in Kenya, with thousands of new cases annually, and many patients presenting late for treatment. In that context, post-surgical support—physical, psychological, and social—can be as critical as surgery itself.

For women leaving hospital without access to expensive prosthetic care, Mwangi’s model offers a low-cost bridge back to everyday life: clothing that fits, confidence in public spaces, and a community that says survivorship does not have to mean isolation.