PORT-AU-PRINCE, Haiti — Haiti’s nine-member Transitional Presidential Council has formally ended its mandate without a confirmed successor structure, creating a new phase of political uncertainty as Prime Minister Alix Didier Fils-Aimé remains in office and is now expected to steer the transition on his own.

The council, created in April 2024 to help stabilize the country, curb gang violence, and prepare long-delayed elections, leaves office after months of internal fractures, corruption allegations, and worsening security conditions. Negotiations over what should replace it are still underway, with no final framework announced at the time of the handover ceremony.

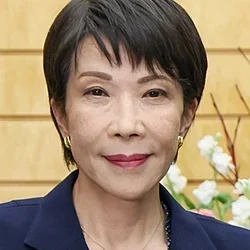

Outgoing council president Laurent Saint-Cyr said leaders needed to set aside personal interests and focus on security, as the body’s final weeks were overshadowed by a failed effort to remove the prime minister. Reuters reported that in January, council members backed away from that attempt after pressure from Washington, which had signaled serious consequences if Fils-Aimé were pushed out.

Fils-Aimé now carries the central burden of organizing Haiti’s first general elections in roughly a decade under extreme insecurity. Haiti last held national polls in 2016 and has had no elected president since Jovenel Moïse’s 2021 assassination. While tentative dates have circulated for an August first round and a December runoff, many observers question whether voting logistics can be secured this year given current violence levels.

The security backdrop remains dire. U.N.-cited figures referenced in current reporting indicate nearly 6,000 people were killed in Haiti last year, while around 1.4 million have been displaced by gang violence. That humanitarian pressure has complicated both governance and election planning, especially in and around Port-au-Prince, where armed groups retain broad territorial influence.

A U.N.-backed multinational security support mission continues to deploy, but Reuters and AP report staffing remains far below planned levels, limiting its ability to rapidly shift conditions on the ground.

For now, Haiti faces a dual vacuum: a dissolved collective leadership model and no settled replacement architecture. The immediate test is whether political actors can build a credible interim arrangement quickly enough to prevent further institutional drift while restoring enough security to make elections feasible.